Estimated Reading Time: 6 minutes

How Quantum theory might shape the future of AI. Did I understand everything? Not even close. But this is my attempt to share what I’ve learned so far, driven by curiosity.

I’ve always been curious about how nature works beneath the surface and how those rules influence the intelligent systems we are building today. The idea that mathematics is the language of nature still amazes me, especially when it ranges from explaining something as simple as melting ice (atoms sitting in harmony) to the precision of atomic clocks that power GPS.

Over time, I found myself reading about time and space, touching on special and general relativity, revisiting the double slit experiment, and eventually encountering Bell’s equations. My goal wasn’t mastery, but intuition, especially around how quantum theory might shape the future of AI.

Let’s get started,

Light is one of the most familiar things in our lives. We see it every day, it helps plants grow and allows us to see the world. For a very long time, scientists argued about what light really is. Some thought light was a wave, like ripples on water. Others thought light was made of tiny particles flying through space. Modern physics discovered something surprising, light is both a wave and a particle. The particle of light is called a photon.

A photon is a tiny packet of energy. It has no mass, it cannot be stopped, and it always moves at the speed of light. Even though photons are particles, they also behave like waves. This wave/particle duality is one of the most important ideas in modern physics.

To understand photons, we must first understand what a wave is. A wave is not an object, it is a movement. When you drop a stone into water, the water does not travel outward, but the ripple does. Sound waves move through air, and light waves move through empty space. Light waves are electromagnetic waves, made of electric and magnetic vibrations moving together.

One important property of light is polarization. As light travels forward, it also vibrates sideways. The direction of this vibration is called polarization. Polarization can be vertical, horizontal, or at any angle. Even though polarization can point in many directions, when we measure it, we always get only two answers, pass or block, yes or no, +1 or −1.

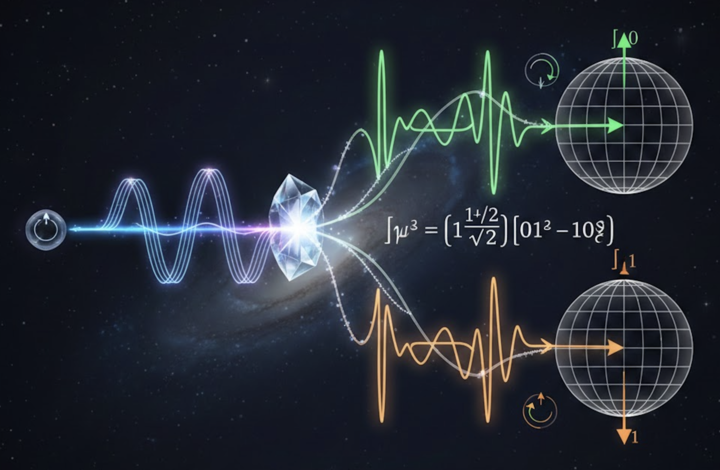

When two photons are created together, something very strange happens. Nature does not give each photon its own independent polarization. Instead, it gives them a shared rule. For example, if one photon is measured as vertical, the other will be horizontal, but which one is which is not decided until measurement. This shared state is called quantum entanglement. At this point, I had to literally take breaks and breathe 😄

Entanglement does not mean the photons send signals to each other. It means they are described by one joint state. You cannot fully describe one photon without the other.

Physicist John Bell asked whether these photons might secretly carry hidden instructions. He proved mathematically that if they did, the correlations between measurements would never exceed a certain limit. That limit is called Bell’s inequality, written as S ≤ 2.

Experiments showed that nature violates this inequality, reaching values close to 2.8 and more. This proves that photons do not carry preexisting individual properties. This is honestly amazing and so not in our common sense.

When one photon is measured, the entanglement is destroyed. The other photon now has a definite state, even if it has not yet been measured. Bell’s experiment works because it studies statistics across many fresh entangled pairs, not a single pair.

To visualize a single photon, physicists use the Bloch sphere. Each possible quantum state is represented as a point on the surface of a sphere. Measurement is like projecting the arrow (for the point) onto a chosen axis. The probabilities depend on angles, which is why cosine appears so often in quantum physics. The Bloch sphere applies to only one photon. Entangled photons cannot be drawn as two separate arrows. They must be described together as a single quantum object.

The deepest lesson is that the universe is not built from tiny objects with fixed properties, but from relationships that only become real when we interact with them. Yes, it is crazy and proven!

Quantum Computing Explained Through Database Search

Imagine you are searching for a single correct answer hidden in a very, very large database. The database could contain passwords, images, phone numbers, or solutions to a math problem. You do not know where the correct answer is, you only know that one correct answer exists.

In a normal computer, this problem is simple but slow. The computer checks entries one by one. If there are 1 million entries, it may need to check about half a million before it finds the right one. This is how classical computing works, step-by-step checking.

Quantum computing approaches this problem in a completely different way. To understand how, we must first understand photons, waves, polarization, and entanglement. Read above.

Although we discussed this above, to stay connected, I am repeating it here. Light is made of tiny particles called photons. A photon is a packet of energy that always moves at the speed of light. Even though it is a particle, it also behaves like a wave. This wave nature allows photons to spread out and interfere with themselves. A wave is not an object, it is a motion. Water waves move on the surface of water, sound waves move through air, and light waves move through space. Light waves are electromagnetic waves. As these waves move forward, they also vibrate sideways. The direction of this vibration is called polarization.

Polarization can point in many directions. However, when we measure the polarization of a photon, we always get only one of two outcomes,w pass or block, yes or no. These two outcomes are used to represent information in quantum computing.

In quantum computing, information is stored in qubits. A qubit can be made using photons, where polarization represents the qubit state. Unlike classical bits, qubits can exist in superposition. Superposition means a qubit can represent many possibilities at once. This is visualized using the Bloch sphere. Every point on the surface of the Bloch sphere represents a possible qubit state.

To search a database of N entries, we use n qubits such that 2^n ≥ N. By placing all qubits into superposition, the quantum computer represents all database entries at once as a probability wave.

At this stage, the qubits are entangled. This means the information is stored across the whole system rather than in individual qubits.

To identify the correct answer, the quantum computer uses an oracle (for me, it is equivalent to a programming function that evaluates a condition). The oracle does not measure or read the answer. It simply applies a rule that flips the phase of the correct answer.

This phase flip does not reveal information. After the oracle, the quantum computer applies interference operations. These operations increase the probability of the correct answer while reducing the probability of incorrect answers.

Each oracle interference pair is called a Grover iteration. About √N such iterations are needed. After these steps, the correct answer has a very high probability. Only then does the computer perform measurement. Measurement collapses the quantum wave into a classical result. Each qubit produces a 0 or 1, forming a binary number that points to the database entry.

Measurement destroys entanglement, which is why it must be done at the end. The key insight is that quantum computers do not search by checking answers. They search by reshaping probability using waves and interference. This approach works because nature allows entanglement and wave interference, as proven by Bell’s experiments.

Quantum computing is not magic. It is nature performing computation according to the rules of the quantum world.

Artificial Intelligence

Using quantum logic, can I store AI model weights and perform inference at very low cost while being more performant?

Artificial intelligence systems today are built by storing and processing very large numbers of parameters called weights. These weights are learned from data and stored in classical memory, then reused repeatedly during inference. A natural question is whether quantum logic could store these weights more efficiently using superposition and entanglement, thereby performing inference faster and more cheaply. While this idea is tempting, quantum physics places strict limits on how information can be stored and read. Although a quantum state can mathematically contain many amplitudes at once, those amplitudes cannot be directly accessed. Measurement returns only one result at a time, which means a quantum state cannot serve as classical memory for AI models.

Where quantum logic does show promise is not in replacing neural network inference, but in accelerating certain types of computation that AI relies on. Quantum systems are especially good at exploring large spaces, reshaping probability distributions, and finding structure through interference. This makes them potentially useful for optimization tasks such as hyperparameter tuning, combinatorial search, scheduling, routing, and sampling difficult energy landscapes. In these cases, the quantum computer does not store the AI model itself, but helps guide or accelerate parts of the learning or decision making process.

Another realistic direction is hybrid classical quantum AI, where classical hardware continues to store and evaluate neural networks, while small quantum processors serve as specialized accelerators. This is similar to how GPUs are used today, but with a much narrower role. For example, a quantum device might be used to sample from a complex distribution, solve a constrained optimization subproblem, or speed up a specific linear algebra step, while the rest of the AI pipeline remains classical. This approach avoids the fundamental problems of loading data into quantum states and reading results back out.

The key insight is that quantum computers excel at global, wave like computation, while modern AI relies heavily on stable, reusable numerical memory. These strengths do not naturally overlap. As a result, quantum computing is unlikely to make AI inference cheap in the near term, but it may become a powerful complementary tool for optimization, search, and decision making within larger AI systems.

😄 I tried to understand photons, entanglement, Bell’s equations, quantum search, and AI. The result is a superposition of curiosity and confusion, collapsed only by coffee and holidays.